Ep #76: Tuning Postgres: The Art of Vacuum, Fillfactor, and Advanced Indexing

Moving beyond CREATE INDEX: How to optimize Postgres for high-velocity updates and massive datasets.

Breaking the complex System Design Components

By Amit Raghuvanshi | The Architect’s Notebook

🗓️ Jan 22, 2026 · Deep Dive ·

The MVCC Trap & Fillfactor

The Postgres Quirk: MVCC Most developers treat Postgres like a black box: put data in, get data out. But Postgres has a unique architecture called MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control). When you UPDATE a row in Postgres, it does not overwrite the old data. Instead, it:

Marks the old row (tuple) as “dead.”

Inserts a new version of the row.

Updates all indexes to point to the new location.

This means every UPDATE is actually an INSERT. This leads to two massive problems: Table Bloat (dead rows taking up space) and Write Amplification (updating indexes unnecessarily).

If you have a table with 10 indexes, and you update the last_login column, Postgres has to update all 10 indexes to point to the new row location, even if the other indexed columns didn’t change. This is massive Write Amplification.

As part of this post we will fix your Postgres configuration to handle high-velocity updates without bloating your disk.

Here are 4 strategies to fix this.

Strategy 1: Tuning FILLFACTOR (The “Elbow Room” Strategy)

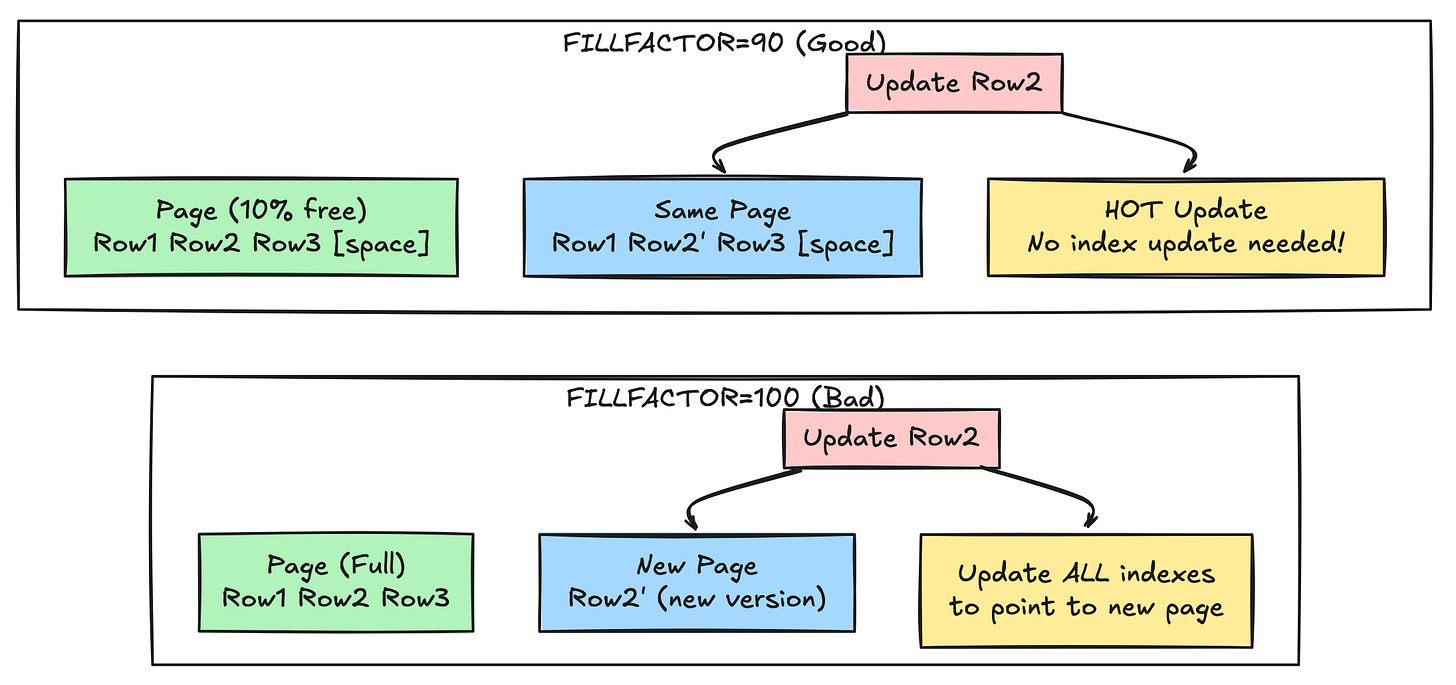

By default, Postgres packs data pages 100% full (FILLFACTOR = 100). This is great for read-only data, but terrible for updates.

The Scenario: You have a page that is 100% full. You update one row. Because the page is full, the new version of the row cannot fit on the same page. Postgres has to write the new row to a completely different page on the disk. Because the row moved pages, Every Single Index pointing to that row must be updated to point to the new page address.

The Fix: Set FILLFACTOR to 80 or 90 for write-heavy tables.

ALTER TABLE users SET (fillfactor = 90);This tells Postgres: “Only fill pages up to 90%. Leave 10% empty.” Now, when you update a row, Postgres places the new version in that 10% empty space on the same page.

The Magic: HOT Updates (Heap Only Tuples) If the new row stays on the same page, Postgres creates a HOT Update. It does not need to update the indexes. It simply updates a pointer on the page header.

Without HOT: Update Heap + Update 5 Indexes.

With HOT: Update Heap only. Result: 80% reduction in I/O for update-heavy workloads.

When to Use Different FILLFACTOR Values

-- High-frequency updates (e.g., session tracking, real-time counters)

ALTER TABLE sessions SET (fillfactor = 70);

-- Moderate updates (e.g., user profiles)

ALTER TABLE users SET (fillfactor = 85);

-- Mostly reads, rare updates (e.g., product catalog)

ALTER TABLE products SET (fillfactor = 95);

-- Append-only (e.g., immutable logs)

ALTER TABLE audit_logs SET (fillfactor = 100);Monitoring HOT Updates

Check if your updates are benefiting from HOT:

SELECT

schemaname,

tablename,

n_tup_upd,

n_tup_hot_upd,

ROUND(100.0 * n_tup_hot_upd / NULLIF(n_tup_upd, 0), 2) AS hot_update_ratio

FROM pg_stat_user_tables

WHERE n_tup_upd > 0

ORDER BY hot_update_ratio ASC;Goal: Hot update ratio > 80% for frequently updated tables.

Strategy 2: Partial Indexes (The “Sniper” Strategy)

Stop indexing everything. Use Partial Indexes to index only the rows you actually query.

Scenario: Orders Table You have an orders table with 10 million rows. 95% of orders are completed, and you never query them. You only query pending orders (the active 5%).

Bad Index:

CREATE INDEX idx_status ON orders(status);

-- Indexes ALL 10 million rows. Huge size. Slow writes.Good Index:

CREATE INDEX idx_pending ON orders(status) WHERE status = ‘pending’;

-- Indexes only 50k rows. Tiny size. Fast writes.The Partial Index is:

Smaller: 50k rows vs 10M rows, Fits in RAM easily.

Faster to read: Less data to scan

Faster to Write: If you insert a

completedorder, the index is ignored. Zero write overhead. Only updated when status changes to/from ‘pending’

More Partial Index Examples

Active users only:

CREATE INDEX idx_active_users ON users(last_login)

WHERE active = true;Recent orders:

CREATE INDEX idx_recent_orders ON orders(created_at)

WHERE created_at > NOW() - INTERVAL ‘30 days’;High-value transactions:

CREATE INDEX idx_high_value ON transactions(amount)

WHERE amount > 10000;Performance Impact Example

-- Before: Full index

CREATE INDEX idx_all_orders_status ON orders(status);

-- Size: 450 MB

-- Write overhead: Every insert updates index

-- After: Partial index

CREATE INDEX idx_pending_orders ON orders(status)

WHERE status IN (’pending’, ‘processing’);

-- Size: 12 MB

-- Write overhead: Only 5% of inserts update index

-- Result: 97% reduction in index size

-- 95% reduction in write overheadStrategy 3: Covering Indexes (Index-Only Scans)

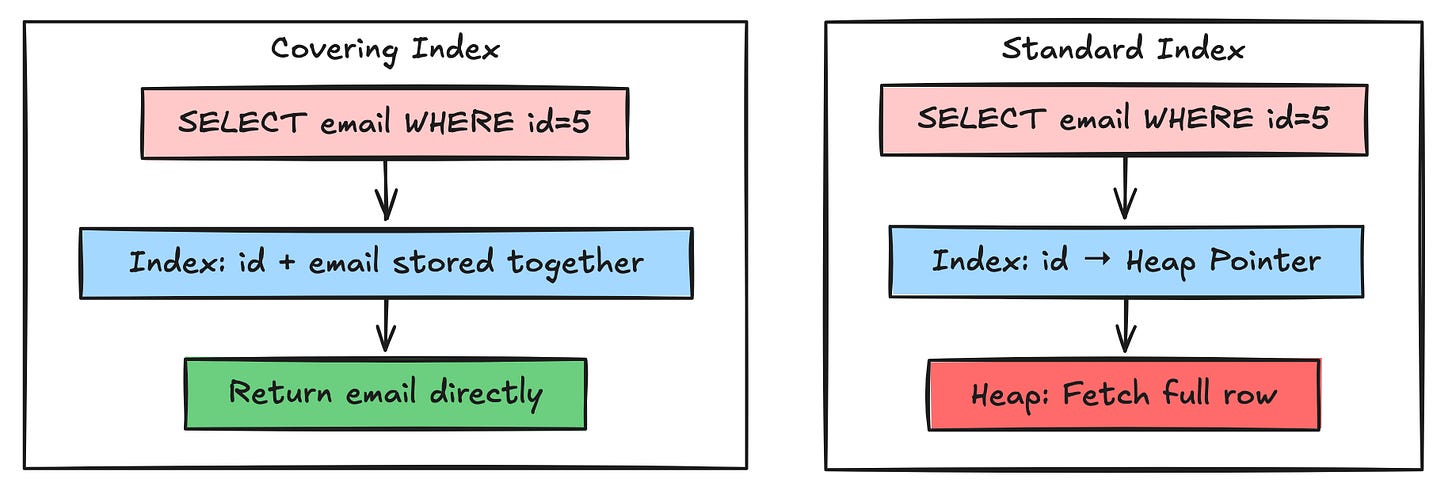

If a query is very frequent, include the “payload” data in the index itself using the INCLUDE clause.

Example Query

SELECT email FROM users WHERE id = 5;Standard Index:

Postgres finds

id = 5in the B-TreeJumps to the Heap (Disk) to fetch the

email2 disk reads

Covering Index:

CREATE INDEX idx_id_email ON users(id) INCLUDE (email);Now, the email is stored inside the B-Tree leaf node. Postgres answers the query purely from the index without ever touching the main table (Heap). 1 disk read.

When to Use Covering Indexes

Good candidates:

Small additional columns (IDs, booleans, short strings)

Frequently executed queries

Columns already in SELECT but not in WHERE

Bad candidates:

Large columns (TEXT, JSON, arrays) — bloats index

Rarely queried columns

Columns that change frequently (defeats HOT updates)

Real-World Example

-- Common query: Get user email and username by ID

SELECT email, username FROM users WHERE id = ?;

-- Covering index

CREATE INDEX idx_users_lookup ON users(id) INCLUDE (email, username);

-- Performance gain:

-- Before: 2 disk I/O (index + heap)

-- After: 1 disk I/O (index only)

-- 50% reduction in I/OVerify Index-Only Scan

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS)

SELECT email FROM users WHERE id = 12345;Look for: Index Only Scan in the query plan.

Strategy 4: Composite Index Strategy (Column Order Matters)

The order of columns in a composite index is critical. Postgres can only use an index if your query matches the leftmost prefix.

The Rule: High Selectivity First

-- Good: Status (4 values) then user_id (millions)

CREATE INDEX idx_bad ON orders(status, user_id);

-- Better: user_id (high selectivity) then status

CREATE INDEX idx_good ON orders(user_id, status);Why? The first column narrows down the search space. If you search by user_id, you immediately eliminate 99.99% of rows. Then filtering by status is cheap.

Leftmost Prefix Rule

CREATE INDEX idx_composite ON orders(user_id, status, created_at);

-- ✅ These queries can use the index:

WHERE user_id = 5

WHERE user_id = 5 AND status = ‘pending’

WHERE user_id = 5 AND status = ‘pending’ AND created_at > ‘2024-01-01’

-- ❌ These queries CANNOT use the index:

WHERE status = ‘pending’ -- Skips user_id

WHERE created_at > ‘2024-01-01’ -- Skips user_id and status

WHERE status = ‘pending’ AND created_at > ‘2024-01-01’ -- Skips user_idMulti-Index Strategy

If you need to query by different column combinations, create multiple indexes:

-- For: WHERE user_id = ? AND status = ?

CREATE INDEX idx_user_status ON orders(user_id, status);

-- For: WHERE status = ? AND created_at > ?

CREATE INDEX idx_status_date ON orders(status, created_at);

-- For: WHERE created_at > ?

CREATE INDEX idx_created_at ON orders(created_at);Yes, this increases write overhead. Balance is key.

🔒 Subscribe to read the Advanced Tuning Guide

We have optimized the table layout. Now we need to optimize the cleanup process.

Postgres creates “dead rows.” Something needs to clean them up. That something is VACUUM. If you don’t tune it, your database will bloat until it runs out of disk space.

In the rest of this deep dive, we will cover:

Advanced Index Types: When to use

BRIN(for massive time-series data) andGIN(for JSONB/Arrays).Vacuum Tuning Checklist: The specific

autovacuumsettings you need to change to prevent bloat.Bloat Detection: SQL queries to find out which indexes are wasting space.

Zero-Downtime Migration: How to use

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLYsafely in production.