Ep #67: Eventual Consistency in Distributed Systems: Understanding Database Replication and CAP Theorem | Part 1

Learn why your likes disappear, how database replication lag works, and when to choose eventual consistency over strong consistency in distributed systems.

Breaking the complex System Design Components

By Amit Raghuvanshi | The Architect’s Notebook

🗓️ Dec 16, 2025 · Deep Dive ·

The “Disappearing Like” Mystery

We have all experienced it.

You are scrolling through Twitter (or X, or LinkedIn). You see a post you agree with. You hit the “Like” button. The heart turns red. You feel good.

Then, you refresh the page.

The heart is gray again. Your like has vanished. You panic slightly—did the internet disconnect? Did the app crash? You click it again. Now it stays red.

Congratulations. You have just met Eventual Consistency in the wild.

For Junior Engineers, this behavior looks like a bug. For Senior Engineers, this behavior looks like a Trade-off.

In the world of System Design, “Eventual Consistency” is often thrown around as a magic wand to excuse bad data hygiene. “Oh, don’t worry if the data is wrong, it’s eventually consistent!”

But what does that actually mean? Does it mean the data will be correct in 5 milliseconds? 5 minutes? Or whenever the server feels like it?

Today, we are going to demystify the mechanics of Eventual Consistency. We will look at why we need it, how it breaks, and the specific “flavors” of consistency that separate a usable app from a chaotic mess.

The Physics of Data: Why Can’t We Have Nice Things?

To understand Eventual Consistency, you have to understand the physical limitations of a distributed system.

In the old days (The Monolith Era), we had one database server.

Write: UPDATE users SET coins = 50

Read: SELECT coins FROM users -> Returns 50.It was instant. It was Strongly Consistent. Time was linear.

But one server can’t handle the traffic of Instagram or Uber. So, we add more servers. We introduce Replication.

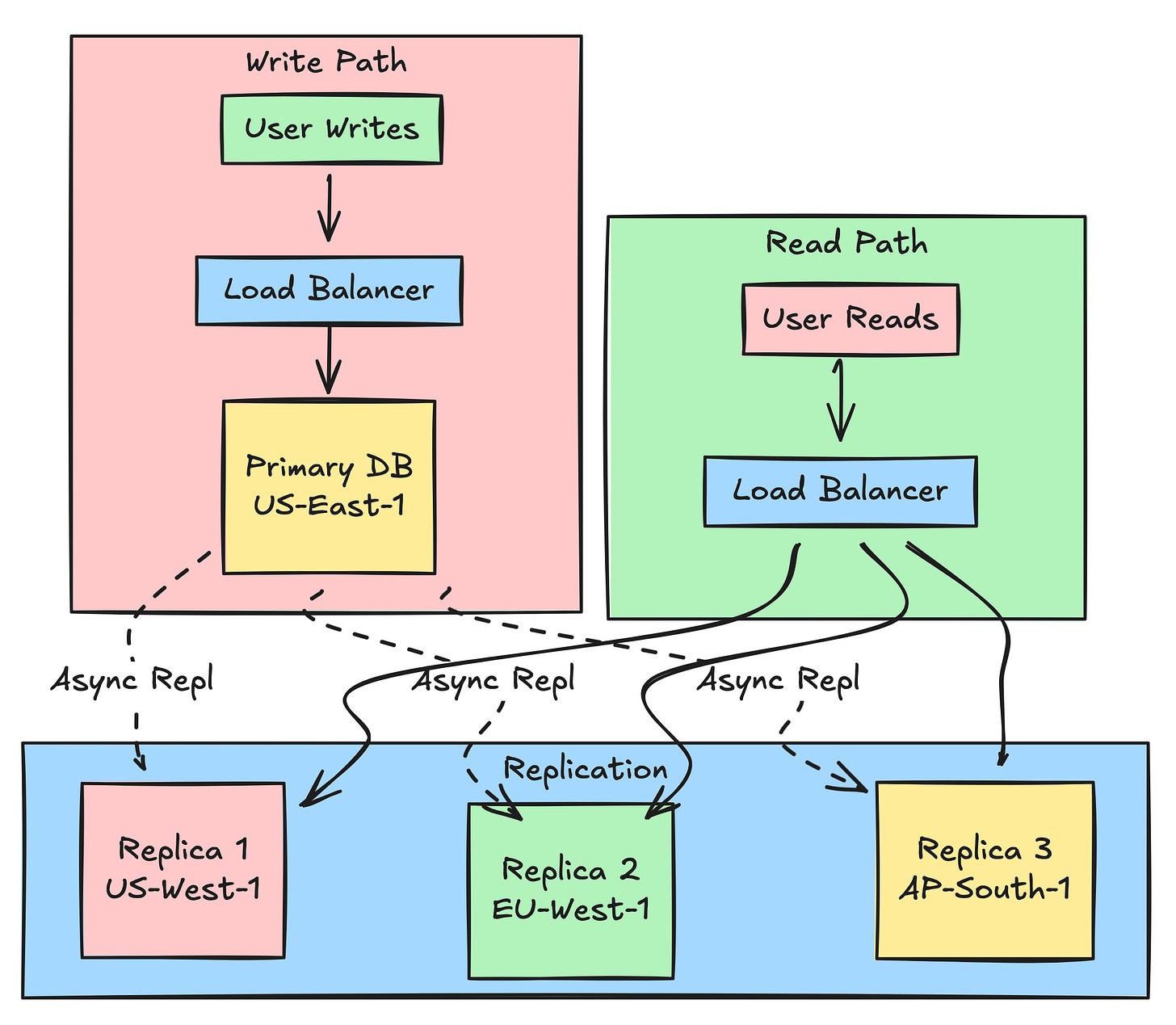

Usually, we have one Primary (Leader) node that accepts writes, and multiple Replica (Follower) nodes that handle reads. This allows us to scale reads to millions of users.

But here is the catch:

Light has a speed limit.

When you write to the Primary node in Virginia (US-East-1), that data has to travel over fiber optic cables to the Replica node in Ireland (EU-West-1). That takes time.

If a user in Ireland reads from the Irish Replica before the data arrives, they see the old data.

This gap in time—between the write happening on the Primary and the write appearing on the Replica—is the Replication Lag. That lag is the window of “Eventual Consistency”.

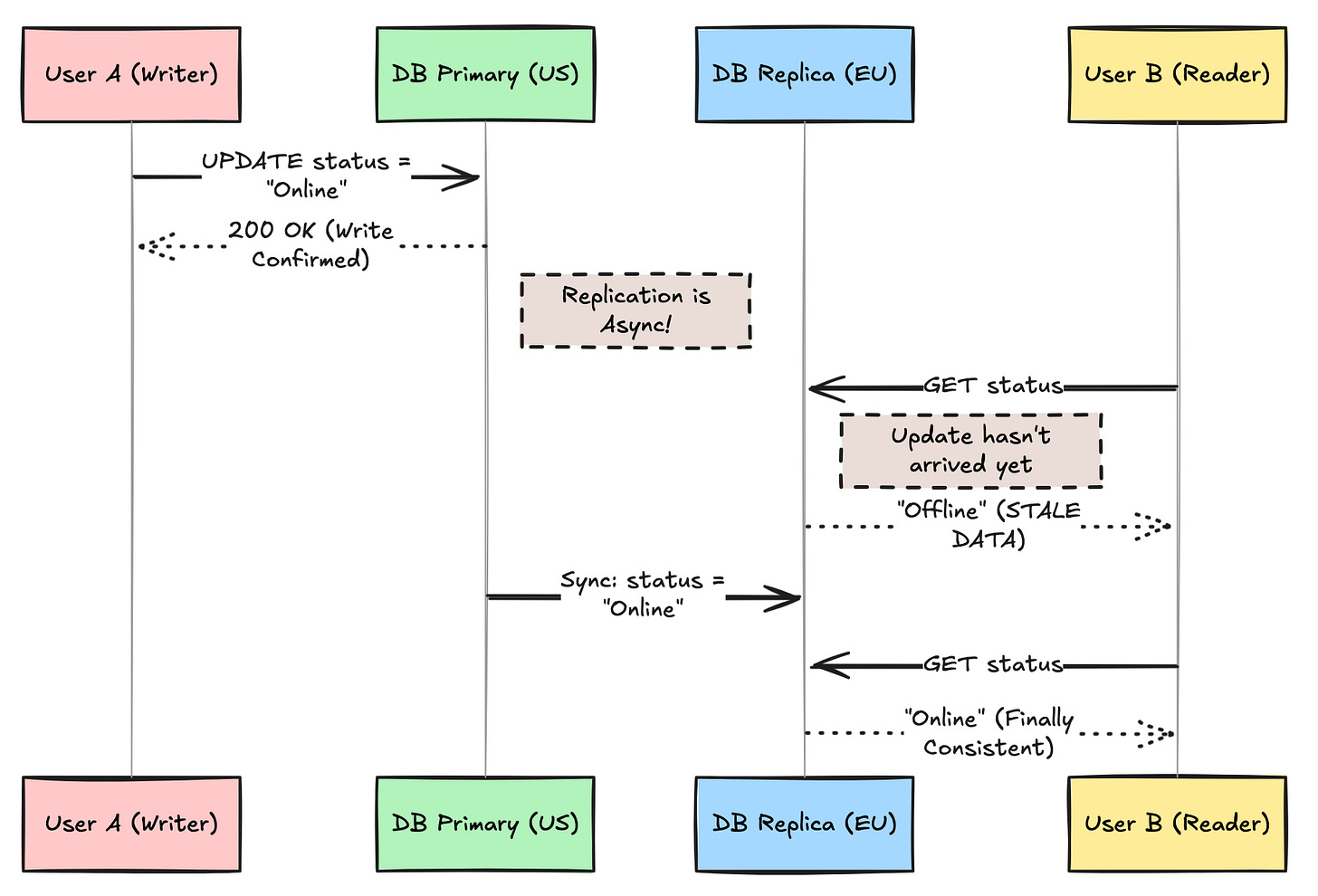

Visualizing the Problem

In the diagram above, User B saw “Offline” even though User A had already successfully changed their status to “Online”. For a few hundred milliseconds, the system was inconsistent.

📚 Level Up Your Architecture Skills

I have condensed years of high-scale engineering experience into my System Design Masterclass series. These aren’t textbooks; they are interview simulations designed to move you from Senior to Staff Engineer.

Volume 1: Building Financial Systems That Never Fail

Focus: Idempotency, Sagas, and Double-Entry Ledgers.

Goal: Correctness.

Volume 2: Building Inventory Systems That Survive the Crush

Focus: Pessimistic Locking, Redis Atomicity, and Virtual Waiting Rooms.

Goal: Extreme Concurrency.

For readers of this newsletter, I’m offering a flat 15% discount for a limited time.

[Download Volume 1] | [Download Volume 2] [Download Beyond the Resume]

The Real-World Numbers: How Long Is “Eventually”?

Let’s talk concrete numbers, because “eventually” is dangerously abstract.

In a typical cloud setup with asynchronous replication:

Same data center, different racks: 1-5 milliseconds

Cross-region (US-East to US-West): 50-100 milliseconds

Cross-continent (US to Europe): 100-200 milliseconds

Cross-continent with network congestion: 500ms to several seconds

During a network partition or outage: Minutes to hours (or never, until manual intervention)

For social media likes? 100ms is invisible. For a trading platform executing a $1 million order? 100ms is an eternity where prices can swing dramatically.

The “eventually” in Eventual Consistency is not a bug in your code. It is the speed of light mixed with the chaos of network reliability.

The Architecture: Master-Slave Replication

Let’s break down the most common replication pattern that introduces eventual consistency.

The Flow:

All writes go to the Primary (single source of truth)

Primary logs the change and responds “OK” immediately

In the background, Primary ships changes to Replicas

Reads are distributed across all Replicas (horizontal scaling)

If a Replica hasn’t caught up yet, it returns stale data

This is called Asynchronous Replication and it’s the foundation of Eventual Consistency.

The Definition: A Promise, Not a Fact

The formal definition of Eventual Consistency (from the BASE model) is essentially this:

“If no new updates are made to a given data item, eventually all accesses to that item will return the last updated value”.

Read that carefully. “If no new updates are made.”

It doesn’t guarantee when. It doesn’t guarantee order. It just guarantees that if everyone stops talking, the system will eventually agree on the truth.

But in a high-velocity system (like a stock market or a multiplayer game), updates never stop. So, “eventually” can effectively feel like “never.”

BASE vs. ACID: The Great Database Philosophy War

To understand why Eventual Consistency exists, you need to understand the two competing philosophies in database design:

ACID (Traditional SQL Databases)

Atomicity: All or nothing. A transaction either completes fully or not at all.

Consistency: The database moves from one valid state to another. No broken rules.

Isolation: Concurrent transactions don’t interfere with each other.

Durability: Once committed, data survives crashes.

BASE (NoSQL / Distributed Systems)

Basically Available: The system guarantees availability (it will respond to requests).

Soft state: The state of the system may change over time, even without input (due to eventual consistency).

Eventual consistency: The system will become consistent over time, given that the system doesn’t receive input during that time.

ACID is a lawyer. Everything is documented, verified, and legally binding.

BASE is a startup founder. Move fast, fix things later, just keep the lights on.

Neither is wrong. They solve different problems.

Here’s a quick TL;DR video summary of this article — perfect if you prefer watching instead of reading

The Tradeoff: Why Do We Choose This Pain?

If Eventual Consistency leads to stale reads and confused users, why do we use it? Why not just force the Primary to update all Replicas before confirming the write?

Because of the CAP Theorem (or more accurately, the PACELC theorem).

Understanding CAP Theorem

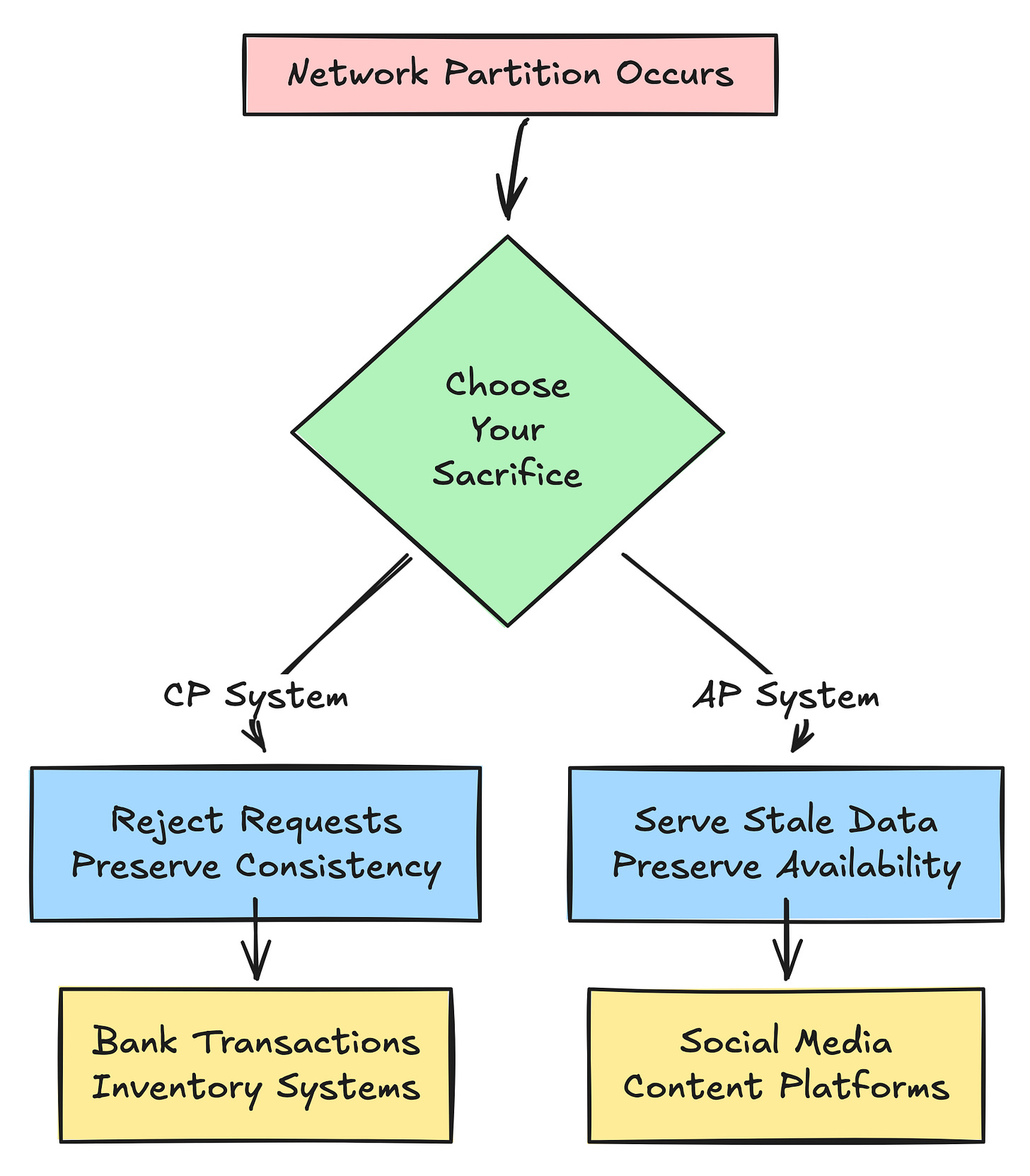

CAP Theorem states that in a distributed system, you can only guarantee 2 of 3:

Consistency: Every read receives the most recent write

Availability: Every request receives a response (without guarantee it’s the latest)

Partition Tolerance: System continues operating despite network failures

Since network partitions are inevitable (you can’t avoid them), you are forced to choose:

CP (Consistency over Availability): If the connection between US and EU breaks, the system refuses to answer queries to prevent showing stale data. The site goes down for European users.

AP (Availability over Consistency): If the connection breaks, the system keeps answering queries. The European users might see old data, but at least the site loads.

For 99% of consumer applications, Availability > Consistency.

If Amazon shows you a book price that is 5 minutes old, nobody dies.

If Amazon refuses to load the page because the database is syncing, they lose millions of dollars.

We choose Eventual Consistency because Latency is the enemy of Conversion. Waiting for strong consistency (synchronous replication) makes your app slow. Slow apps lose users.

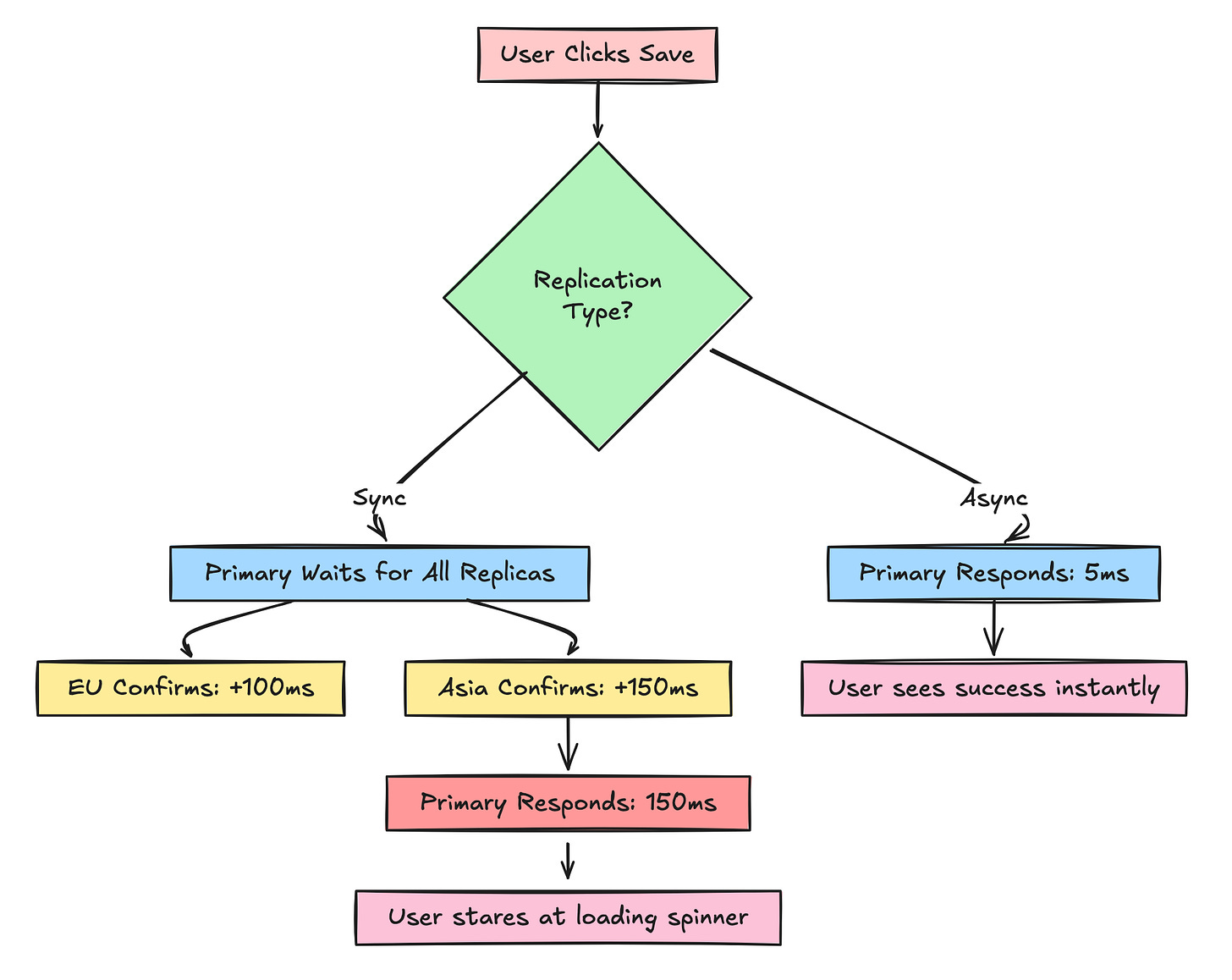

The Hidden Cost: Synchronous Replication

Let’s make this concrete with an example.

Scenario: You have 3 replicas (US, EU, Asia).

Asynchronous Replication (Eventual Consistency):

User writes to Primary in US

Primary responds “200 OK” immediately (5ms)

Primary sends data to EU and Asia in the background

Total user-facing latency: 5ms

Synchronous Replication (Strong Consistency):

User writes to Primary in US

Primary sends data to EU (100ms) and Asia (150ms)

Primary waits for both to confirm

Primary responds “200 OK”

Total user-facing latency: 150ms

That’s 30x slower. In web performance, that’s the difference between “instant” and “feels broken.”

Real-World Case Studies: When It Goes Wrong

Case Study 1: The GitHub Outage (2012)

What Happened: GitHub’s MySQL replication lagged during a datacenter migration. A developer pushed code to a primary database, but the replica was 3 seconds behind. A deploy script read from the replica, saw old code, and deployed the wrong version to production.

Impact: Site down for 2 hours. Millions in lost productivity.

The Fix: They implemented “read-your-writes” consistency for critical deploy operations, forcing reads from the primary during deployments.

Lesson: Deploy scripts, migrations, and CI/CD pipelines should NEVER read from eventually consistent replicas.

Case Study 2: The Instagram “Disappearing Photos” (2016)

What Happened: Instagram’s Cassandra cluster had replicas lagging by up to 30 seconds. Users would upload a photo, the app would confirm success (written to one node), but when they refreshed, the photo was gone (reading from a different, lagging node).

Impact: User complaints surged. Instagram was accused of censorship and bugs.

The Fix: They implemented sticky sessions, ensuring users always read from the same replica pool for 60 seconds after any write. They also improved monitoring of replication lag and auto-removed replicas that lagged by more than 10 seconds.

Lesson: User experience demands read-your-writes consistency for user-generated content.

The Solution Landscape: 4 Flavors of Consistency

Now that you understand the problem, you need to know the solution space. Consistency isn’t binary—there’s a spectrum of guarantees you can provide:

Read-Your-Writes Consistency: Users see their own changes immediately

Monotonic Reads: Time never goes backward for a user

Causal Consistency: If A causes B, everyone sees A before B

Strong Eventual Consistency (CRDTs): Mathematical conflict-free convergence

Each has different implementation strategies, performance characteristics, and use cases, and we are covering the same in the Paid section below.

Conclusion 1: Knowing When to Compromise

Eventual Consistency is not a bug. It’s a deliberate architectural choice driven by the laws of physics (speed of light) and economics (user patience).

Key Takeaways from Part 1:

Eventual Consistency exists because light has a speed limit and synchronous replication is slow

You must choose between Consistency and Availability during network partitions (CAP Theorem)

Some domains (money, inventory, security) can never be eventually consistent

Real companies have lost millions by misunderstanding these tradeoffs

There are multiple “flavors” of consistency between “eventual” and “strong”

Understanding the problem is half the battle. In Part 2, we’ll dive deep into the solutions: Quorum reads, monitoring strategies, and battle-tested implementation patterns that make eventual consistency invisible to your users.

You’ll learn exactly how Twitter makes likes feel instant, how Google Docs handles concurrent edits, and how to test your system for consistency violations before they hit production.

🔒 Subscribe to Master Data Consistency

We have defined the problem: We trade correctness for speed.

But how do we stop our users from feeling like the app is broken? You cannot just tell your Product Manager “It’s physics, deal with it.” You need engineering patterns to mask this complexity.

In the rest of this deep dive, we will cover:

The 4 Flavors of Consistency: It’s not just On/Off. We’ll look at Monotonic Reads and Causal Consistency.

The “Read-Your-Writes” Pattern: The exact caching strategy used by Instagram and Facebook to trick users into thinking the app is instant.

Code Implementation: A Python/Redis implementation of Sticky Sessions to solve replication lag.

Database Tuning: How to configure PostgreSQL and MySQL to balance this trade-off.